.

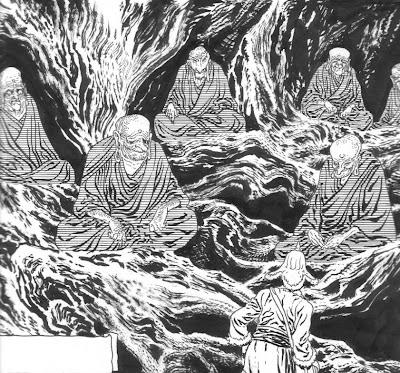

En "Shankar", la serie en la que con Eduardo hemos estado trabajando estos últimos años, paseamos al protagonista por un exótico Oriente alternativo. En las aventuras que corre en China, aparecen a veces como elemento puramente decorativo, y otras como participantes directos en la historia, los Arhat.

"Arhat" es un vocablo sánscrito que puede traducirse aproximadamente como "digno" (la versión china de esta palabra, "Lohan", tiene el mismo significado). Eran conocidos por ese nombre los santones discípulos del Buda que habían alcanzado el Nirvana o Iluminación. Ahora bien, lo que siempre me llamó la atención era la manera en la que eran representados en el arte.

Son extremadamente grotescos, y hasta feos. Acostumbrados en nuestra cultura occidental a asociar la fealdad con el mal y la belleza con el bien ( fíjense en las imágenes de los santos cristianos, de rasgos idealizados que trasuntan bondad y compasión), encontramos a los Arhat inquietantes, sobrecogedores o payasescos, según el caso. Y quedan de este modo patente las diferencias culturales y estéticas entre Oriente y Occidente. En Asia, ese aspecto fiero y montaraz refleja la fuerza indómita del espíritu despierto, de la determinación que abate las sombras de la Ilusión. Una y otra vez , en el budismo Theravada, el Mahayana y el Tántrico, en China, Japón, Tíbet y Corea, nos topamos con santos o deidades de aspecto amenazador, y hasta monstruoso ( ya mostraré otros trabajos en el que empleo esa iconografía), en los que la traza feroz y aterradora, paradójicamente para nosotros, no simboliza lo demoníaco, sino la voluntad inquebrantable que triunfa sobre el mal, y el temor sagrado que estas cerriles divinidades benéficas inspiran en las hordas de espíritus malvados.

In "Shankar", the series which Eduardo and I have worked on for the last few years, the weird adventures of our protagonist in an exotic alternative Orient are told. During his sojourn in China, the Arhat appear, sometimes as a decorative leitmotiv, sometimes as part of the stories themselves.

"Arhat" is a Sanskrit term meaning approximately "worthy"; the Chinese word "Lohan" also refers to that quality. It was the name given to the holy men, disciples of the Buddha, who had attained Nirvana or Enlightenment. What I found curiously disturbing about them is the way they were represented in the visual arts.

They are extremely grotesque, or even ugly. In our Western culture, we associate ugliness with evil, and beauty with the good: just have a look at the icons of Christian saints, of idealized countenances which convey goodness and compassion. Thus it is that we find the Arhat daunting, oddly sinister or ludicrous. So it is, too, that the cultural differences between East and West are evinced. In Asia, that fierce, wild look reflects the indomitable strength of the enlightened spirit, the uncompromising determination which crushes the ominous shadows of Illusion. Time and time again, in Theravada, Mahayana or Tantric Buddhism, in China, Japan, Tibet and Korea, we behold saints and deities of truculent, even monstruous appearance ( I´ll show some examples of this iconography in future posts). The ferocious, fearsome aspect, paradoxically from our Western perspective, does not symbolize the demonic, but the unflinching will which overcomes evil, and the sacred terror that these terrible benevolent entities inspire in the hordes of obnoxious devils.

Todas las imágenes son copyright de Enrique Alcatena